John Buchan, D-Day, spies, pipeweed, Spartan foreign policy, and Father's Day

Weekly digest, June 14, 2025

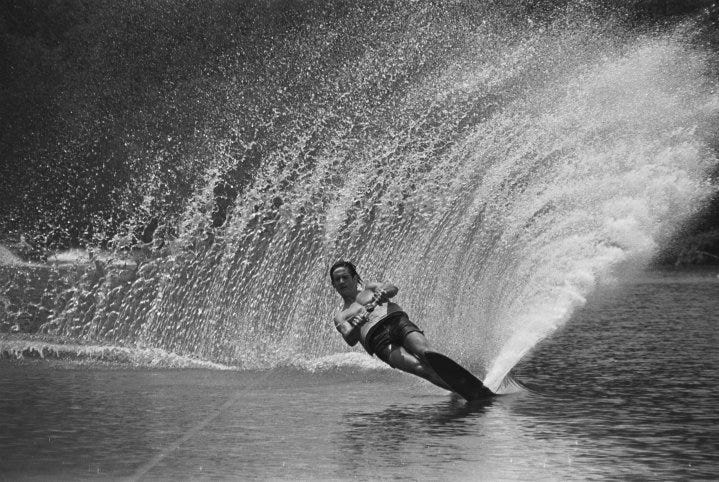

Apologies for no digest last weekend. My family and I had a great vacation, our first full week away together in several years.

Tomorrow is Father’s Day in the US, and, as it happens, my dad’s birthday also falls in the middle of the month, usually on or within a few days of Father’s Day, which makes the holiday especially important to me. He’s one of the few thoroughly good men I have ever known, and I’m blessed to have him in my life. All the other heroes I have—Alfred the Great, Robert E Lee, Cicero, Alvin York—I admire insofar as they resemble him.

Apropos

Two for this week:

There is no higher pleasure in life than to discover in youth a clear aptitude and to look forward to a lifetime to be spent in its development.

—John Buchan in A Prince of the Captivity

And, for Father’s Day, my usual reflection on my own dad:

Manliness without ostentation I learnt from my father.

—Marcus Aurelius

What’s going on

Of interest

At Law & Liberty, Ralph Defalco reviews The Spy and the State: A History of American Intelligence, by Jeffrey P Rogg:

This work explores the USIC’s history by examining US intelligence in each of four wartime eras: the Revolutionary War to the Civil War; the Civil War to the end of World War II; the Cold War; and the present, post-Cold War era. This approach is more than a nod to the march of time. It acknowledges the dominant role military intelligence played in creating the USIC. . . . With the era-by-era approach, the author illustrates how the changing nature of the US role in the world led to the establishment of the nation’s permanent intelligence community.

One of my greatest historiographical interests is periodization, and Rogg’s division here strikes me as an excellent way to break up this story. Going to have to read this.

Also at Law & Liberty, David Lewis Schaefer takes the unveiling of “an artwork about monuments” in Times Square to ask “What is Public Art For?”

I habitually use discussion of modern art as a chance to recommend Tom Wolfe. The Painted Word may be relevant here, but so is his acid takedown of modern architecture, From Bauhaus to Our House.

Here on Substack,

shares a guide to reading and understanding the titles of classical pieces. I had a wonderful music teacher in elementary school so despite my limited technical understanding of music, there’s a lot of this that I do understand thanks to her. This is a very helpful guide to everything from keys and movements to catalog numbers, including some of the more technical aspects that continue to elude or confuse me.Also on Substack,

at shares “The Truth About Pipeweed” in Tolkien’s Middle-earth and is refreshingly to the point. No, pipeweed is not pot. I’ve always taken it for granted that pipeweed is just tobacco—Tolkien clearly states it both within the stories and in his extensive appendices, prologues, and other apparatus—so the persistence of people interpreting it as marijuana has always struck me as perverse.On YouTube, Adrian Goldsworthy, my favorite Roman historian but also the author of the excellent recent novel Hill 112 about D-Day and the Battle of Normandy, unpacks film depictions of D-Day for a glorious three hours. He hits all the high-profile titles about D-Day like Saving Private Ryan and The Longest Day, major films that feature D-Day like Patton and The Dirty Dozen, as well as more obscure ones like the over-the-top Korean film My Way and the largely forgotten D-Day, the Sixth of June.

Hill 112 is highly recommended, by the way. I reviewed it on the blog just before Christmas.

At The University Bookman, David Talcott reviews Sparta’s Sicilian Proxy War, Paul Rahe’s latest in his ongoing study of ancient Sparta and its strategic interests. Talcott, summarizing Rahe’s guiding thesis, observes that “the way that nations fight and conduct themselves internationally is different depending on the character of the people living under each regime.”

Specifically, Sparta’s

distinctive way of life leads to a distinctive grand strategy and foreign policy, one that is contrary to the stereotype of militaristic nations. Rather than seeking world domination, Sparta was passive on the international scene, unadventurous, and generally unwilling to stray far from home. Instead of seeking to project power outside of their region, they were content in the Peloponnese. Their needs were well provided for, and their way of life did not require many grand things. They were not building big houses, importing fine clothes and perfumes, or serving a god who claimed the entire world as his own. They were content as long as the helots stayed enslaved and no great powers threatened their area. Thus, their militaristic regime was aimed at maintaining a merely regional hegemony. There was, at first, no need for adventuring abroad. They lived in simple homes and sang simple songs; their glory was their character and courage.

And, in sum:

Athens and Sparta were not the same and did not act the same on the international stage. Likewise, nations today are not the same, and we will fail to understand international politics if we fail to analyze different regimes to uncover what they honor and what they love.

This emphasis on culture is refreshing whenever and wherever I come across it. The importance of fundamental cultural variation, that everyone everywhere are not basically the same, is one of the points I try to hammer home most clearly in my classes, especially Western Civ.

Today is the anniversary of one of the most shocking deaths in the Civil War. On June 14, 1864, Confederate General Leonidas Polk was scouting Union positions near Atlanta with other officers. As it happens, Sherman was inspecting the line directly opposite and spotted the group of officers on a hilltop. He personally directed a battery of cannon to fire on the group and Polk took a direct hit, nearly cutting him in half and killing him instantly.

In my novel Griswoldville, Georgie Wax notes the arrival of the story through soldierly gossip, but Sam Watkins, author of the great memoir Co. Aytch, actually saw Polk’s body carried off the field:

He was as white as a piece of marble, and a most remarkable thing about him was, that not a drop of blood was ever seen to come out of the place through which the cannon ball had passed. My pen and ability is inadequate to the task of doing his memory justice. . . . When I saw him there dead, I felt that I had lost a friend whom I had ever loved and respected, and that the South had lost one of her best and greatest generals.

One of the most striking and grisly stories to come out of the war.

Finally, for some humor, last week

shared some interesting news from Florida—US Army Rangers menacing beachgoers!—as well as his observations of Florida weathermen and tips for hurricane preparation.The latest on the blog

My annual John Buchan June blogging event is underway, with the following four books reviewed over the last two weeks.

The Runagates Club, a 1928 collection of short stories as told by some of Buchan’s recurring characters like Richard Hannay and Sir Edward Leithen

John Burnet of Barns, Buchan’s first full-length novel, published in 1898 when he was only 23. A swashbuckling historical adventure on the Scots Borders in the vein of Scott and Stevenson.

Julius Caesar, a short, brisk biography from 1932. I disagree with some of Buchan’s interpretations of Caesar’s character but this is an excellent read.

The Watcher by the Threshold, an early (1902) collection of short stories and novellas all set in “the back-world of Scotland.” Eerie, atmospheric, and thoroughly enjoyable.

The special emphasis this year is on Buchan’s short fiction, which I’ve never really dipped into before. It’s been great so far.

From the blog archives

A few favorites from the last three years of John Buchan June:

From 2024: The Free Fishers, a Buchan deep-cut, this lesser-known novel was his last work of historical fiction and is a high-spirited, rollicking Regency adventure.

From 2023: The Gap in the Curtain, a wonderfully strange kinda-sorta time-travel story in which a group of people get a one-second glimpse of the future. What they do with that bit of foreknowledge is a test of character.

From 2022: Sick Heart River, the last Sir Edward Leithen adventure and Buchan’s powerful final novel, published after his untimely death in 1940.

Currently reading

A Prince of the Captivity, by John Buchan

Religious Freedom: A Conservative Primer, by John D Wilsey

Prayer for Beginners, by Peter Kreeft

The Hobbit, by JRR Tolkien

The High King, by Lloyd Alexander

Recently acquired

My birthday was last week, so this section will be a little longer than usual.

Edgar Allan Poe: A Life, by Richard Kopley—A highly anticipated gift from my wife, who got me Nicholas Shakespeare’s massive biography of Ian Fleming last year.

Vita Nuova and The Divine Comedy, by Dante, new translations by Joseph Luzzi and Michael Palma respectively

Barnaby Rudge, by Charles Dickens

The Dark Frontier, by Eric Ambler

The Corpse in the Waxworks and He Who Whispers, by John Dickson Carr

Salute to Adventurers and The Half-Hearted, by John Buchan

The Extinction of Experience: Being Human in a Disembodied World, by Christine Rosen

XPD and Goodbye Mickey Mouse, by Len Deighton

The Major and the Missionary: The Letters of Warren Hamilton Lewis and Blanche Biggs, Diana Glyer, Ed.

The Life of Chesterton: The Man Who Carried a Swordstick and Pen, by Holly Geiger Lee, illustrated by Nellie Buchanan

Until next time

Again, apologies for the week off, but I hope y’all will find something good to read and think about here. In the meantime, thanks as always for reading! Have a happy Father’s Day!

I’m going to have to get a copy of The Watcher by the Threshold—weird fiction, Buchan, and a thoroughly Tolkienian air ticks a lot of boxes.

Honored for the mention!